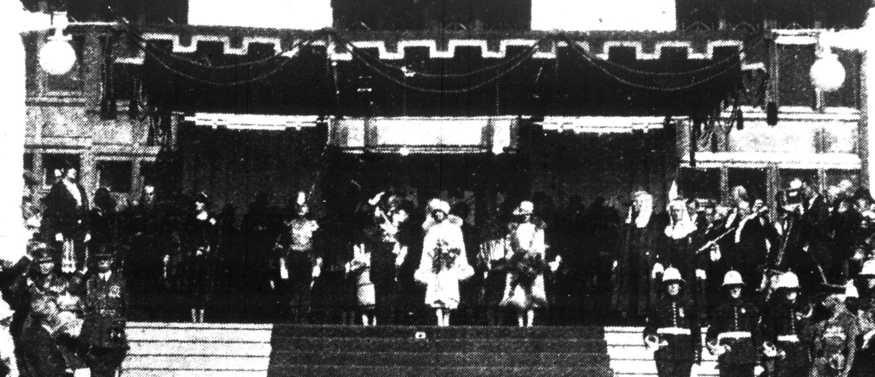

Phonofilming the Duke of York opening

Australia's Federal Parliament

Nellie Melba singing the National Anthem at the opening of Parliament House, Canberra

on 9 May 1927

Melba is on the left, beneath the globe.

In the centre are the Duke (saluting) and Duchess of York.

(Almost beneath the globe on the right is

a Government cinematographer.)

On 26 March 1927, the (English) Duke and Duchess of York arrived at Sydney, New South Wales, Australia to commence a tour of the country, the primary purpose of which was the official opening of the new Federal Parliament House and the inauguration of Federal Parliament at Canberra in the Federal Capital Territory. (Prior to then, Federal Parliament had sat in Melbourne, Victoria.) The arrival of the Duke and Duchess was the subject of motion picture newsreel footage, including some taken by operators of the De Forest Phonofilms (Australia) Limited company using sound-on-film recording apparatus that had arrived in Australia less than 2 weeks earlier. This was the first time this sound-on-film process had been used to make a film in Australia. The results were less successful than had been hoped and planned, but nonetheless demonstrated that it was possible to record image and sound simultaneously. But this first use is another story.

The general manager of De Forest Phonofilms (Australia) was Stanley William Hawkins, a retired army officer who, after World War 1, had set himself up in business in Sydney. He was director of Sovereign Picture Productions, which, at the end of 1926, amalgamated with De Forest Phonofilms (Australia), which itself had been incorporated in 1925. From 6 November through 9 December 1926, overseas-produced phonofilms were shown to the Australian public for the first time at Sydney's Prince Edward Theatre.

Since January 1927, Hawkins had been attempting to get approval from the parliamentary Cabinet committee for the royal visit to phonofilm the proceedings that would take place at Parliament House on 9 May that year. Before approval could be given, he was asked to demonstrate the process to a Government-appointed witness, a position gladly agreed to by Walter A. Gale, Clerk of the House of Representatives. Gale was happy with the foreign-produced phonofilms he was shown, but because delivery from New York of the sound-on-film recording equipment was delayed, he at first could not appraise local operation of the system. Eventually, following the showing at the official opening of the new Phonofilms studios at Rushcutters Bay in Sydney on 6 April, of the films of the arrival in Sydney of the Duke and Duchess of York referred to above, Gale recommended that the company be allowed to film at Canberra.

Unfortunately, the old fogies had been against it from the start. (Cyril) Brudenell B. White, Commonwealth director of the royal visit, had indicated as early as 9 February that the request should be declined. In fact, the committee had decided early on against all forms of sound record of the Canberra ceremonies, including by phonograph records, the first successful local production of which having only been accomplished by the Columbia Gramophone Company in Sydney in August 1926. (One reason given was that they believed the sound would be harsh, like that from radio receivers of the time.) But the De Forest people tried hard to have the committee's decision reversed, including writing a letter to the Prime Minister, Stanley Melbourne Bruce, stressing the historical importance of getting a record in both images and sound. But it was all to no avail. As The Canberra Times newspaper later, on 2 August, put it:

The refusal to the company has been described as appearing to be gross official stupidity in refusing permission for the taking of a complete pictorial and sound record of the ceremony.

Although Walter Gale's report to the Cabinet committee on 9 April was in favour

of allowing Phonofilms to film with sound at the Canberra ceremonies –

I am of the opinion the experiment of reproducing, by means of Talking-Pictures,

the Ceremony at Canberra is well worth making

– there are two incidents

described in it where Hawkins did himself no favour.

Gale said that Hawkins remarked that his Company were not particularly anxious

to reproduce the Opening Ceremony at Canberra

, which, however, Gale then admitted

may be dismissed as merely a little piece of friendly bluff.

Of much more significance though was Gale's report that Captain Hawkins had

previously informed me that the human voice could not yet be perfectly reproduced

;

this would only have increased the concerns of the Cabinet committee who were

already worried about any sound recording of the Duke with his speech impediment.

There were two distinct issues with Phonofilms' request to film at the

Canberra ceremonies but these were not generally distinguished:

(1) filming the events with sound;

and (2) filming inside Parliament House (with sound).

Hawkins specifically asked, in January 1927, to

cinematograph the proceedings in the Federal Parliament House at Canberra

;

it is not known whether or not he was aware at the time that there were also

to be the activities outside to do with the opening of Parliament House itself.

Phonofilms were refused permission to set up their sound recording equipment, but they were given space with the other cinecameramen outside the main entrance of Parliament House and so were able to film, without sound, the speeches and activities that took place as part of the opening of Parliament House. And along with this, they did something very clever: at the company's studio in Sydney their engineer, Alan Mill, phonofilmed the radio broadcast (i.e. sound only) of the events, and the silent images were later combined with the sound recording to produce a phonofilm of some of the speeches. In this way they obtained, according to reports, films with sound of Nellie Melba singing the National Anthem, of the speeches of the Prime Minister and the Duke of York, and of the religious service of dedication.

The ceremony of the inauguration of Federal Parliament at Canberra took place in the Senate chamber inside the new Parliament House, and the De Forest people, along with all other commercial operators, were not allowed there; only the Government's cinematographers were permitted in the Senate chamber. And the reason for this was that there just wasn't enough space available in the room to accommodate any more people.

How well did Hawkins and company do? For a start there were interruptions to the radio broadcast: the microphone was not switched on for a good part of Melba's solo singing of the first verse of the National Anthem, and transmission failed during the concluding portion of the Duke's (outside) speech. Then the synchronisation of the image film with the sound film must have been a major issue, as it would have been most unlikely that the two cameras were running at exactly the same speed. A (probably appropriately) critical review of the film, after it was first shown publicly at Sydney's Lyceum Theatre on 14 May, was published in The Sydney Morning Herald on 16 May:

THE CANBERRA CEREMONIES.

Though the record of the Duke of York's visit to Canberra, which is being shown at the Lyceum Theatre, is called a "phonofilm," the term is only a courtesy title. The essential of the phonofilm proper is the exact synchronisation of sound and image. But in this production the spnchronisation [sic] is such that one sees speakers' lips moving vigorously, while the sound reproducer is silent or in a state of pause while words are coming to the ear. The producers (de Forest Phonofilms, Ltd.) have explained the defect in preliminary captions, setting forth how the Royal Visit Committee refused permission for a phonofilm to be taken, and the company was obliged to reproduce the sound from the broadcasting in Sydney, some 200 miles from the scene of events. Considering these difficulties, the record is interesting, but it is hardly a good advertisement for speaking pictures. Having, apparently, an inadequate amount of ordinary film available, the producers have eked out the aural side of affairs by repeating over and over again on the screen a single incident, occupying perhaps half a minute for its complete course, which shows the Duke slightly raising his hand and inclining his head in response to the applause. There is no perceptible break between one repetition and the next.

This sequence of repetitions gives cause for speculation. Trade journals reported that a phonofilm was made of the Duke's speech in the Senate chamber; but this could only have been the sound of the speech (as broadcast over the radio) because Hawkins and company did not film inside. Did they add the sound of the Senate speech to a film of the Duke that had been taken elsewhere and was repeated as necessary to make up the length of time of the speech?

In subsequent interviews, Hawkins pointed out that no reason had been given to him for the refusal to allow Phonofilms to film with sound, outside or inside. This is probably true, but of course there were reasons, and these were set out in a letter of 19 April 1927 of Thomas William Glasgow, a member of the Cabinet committee, to the committee's chairman. He gave five:

- The Australian-made phonofilms, as reported by Gale from Sydney,

in synchronising the voice with the picture

hadnot been at all satisfactory

. - If they succeeded in getting a good picture but with bad sound, they were

quite capable - being showmen - of faking [the Duke's] voice and in attempting to make it appear genuine they might accentuate his impediment

. - If the sound was not good and only a silent film were released, this would cause trouble with the other companies which had not been permitted to film inside.

- If the Duke of York knew that his speech was being recorded,

it might add to [his] difficulty

. The Opening ceremony is not a function on which we should allow experiments to be tried.

For the first two of these reasons, Hawkins had only himself to blame. Because Phonofilms were unable to get a good sound recording of the Duke's speech of reply to his welcome in Sydney on 26 March, they had dubbed the speech with the voice of someone with an obvious Australian accent! At least there wasn't a stutter in this voice-over.

Littleton Ernest Groom, another committee member, also wrote to the chairman:

It would be a very serious matter if the reproduction were imperfect

and in consequence tended to hold the Ceremony up to ridicule.

On 22 April the committee secretary wrote to Hawkins

that he was directed to inform you that the Royal Visit Cabinet Committee

after careful consideration regrets that it cannot see its way to grant the

desired permission.

Hawkins complained loudly (in the press, at least) about the money De Forest Phonofilms had spent getting the camera and recording equipment to Australia in time: he said that they had paid $1000 in overtime to the laboratory staff in New York.

And despite also complaining about not being able to film with sound, he still boasted that they had made a phonofilm, and he must (at least initially) have felt sufficiently happy with and confident about the finished film because he offered to donate a copy of it to the Commonwealth Government. Even then, they were not content to take it without the agreement of the President of the Senate and the Speaker of the House of Representatives. Ultimately they did agree to accept a copy for the Commonwealth National Library. But in mid-April 1928, Kenneth Binns, the Librarian, wrote to the Government stating that the film had not been received, nor was there any explanation as to why not. De Forest Phonofilms were asked if they had sent a copy, and they replied by saying that the Chairman of Directors of the company, the anything-but-Honorable Thomas John Ley, had been asked to respond. Presumably Ley, who was occupied with serious problems of his own, never did reply, because no further correspondence has been found. And no copy of the film was ever received by the National Library.

It was also reported that the phonofilms of both the Sydney landing ceremony and the Canberra opening were to be shown to the King at a command performance, and that copies of these films had been presented to the King. As there is no record in the Royal Archives of either such a command performance or of a copy for the King, and certainly none has since been found in a UK collection, it also seems likely that no film was sent to the King. So, as no copy of the Canberra film is known to survive, we can only guess at how well it presented such a momentous event in Australia's history.

Thirty-six years after the Canberra opening, Stanley Melbourne Bruce,

who was Prime Minister in 1927, recollected some behind-the-scenes details of the event

in an interview with Cecil Edwards (who later published a biography of Bruce).

It is difficult to square some points in Bruce's recollection with what was

written at and soon after the time of the opening ceremony.

(It should be noted that Bruce was 80 years old at the time of this interview.)

One matter Bruce described with some colour is that on the eve of the opening,

the Duke of York had dug his toes in and said nothing would induce him

to allow them to have the cinema cameras going

, and that Bruce and the Duke

had had a most frightful argument

over the Duke's stand.

Bruce said they reached a compromise in which it was agreed that the

cinecameramen would be able to film everything of the ceremony

except the Duke's speech in the Senate.

(And this thus applied only to the official, Government cameramen because

they were the only ones inside the Senate chamber.)

But it is difficult to understand why the Duke would have been so concerned about being filmed giving his speech. For one thing, both he and the Duchess were keen on movies, and the Duke was interested in the motion picture business. He even had his own Cine Kodak camera with which he took films. In Sydney they had each day viewed at New South Wales Government House the gazette films that had been shot that day by the Paramount cameramen; and they were later given complete films of the tour by Paramount and Australasian Films. And why would he have been concerned about being filmed inside when there were many cameras recording the events outside, with thousands watching?

During the Senate ceremony at least one camera was running, because the National Film and Sound Archive of Australia have a film showing almost 2 minutes of the Duke reading in the Senate chamber (title number 15417). Interestingly, in the Government-produced film of the Senate ceremony there is very little (if even any) footage showing the Duke actually speaking. Admittedly, without sound, it is most uninteresting; the Senate scenes mainly show the various VIPs entering and leaving the chamber.

It is possible that the Duke was more worried about the radio broadcast of

his speeches than about the filming of them.

According to John Wheeler-Bennett's biography, in effect he never did lose

his dislike of public speaking, and especially of broadcasting, ...

.

But at the outside ceremony and in the Senate chamber large microphones were

positioned to pick up the speeches to broadcast to the spectators outside and

for radio transmission.

It appears that Bruce's recollection was somewhat confused;

but if there was a compromise, what was it?

Bruce said he told the Duke:

Well Sir, it's absolutely vital. This is a great historic occasion in Australia. We must have this record.

And what of (the quality of) the speech of the Duke of York? The following very diplomatic comments from The Sydney Morning Herald of 6 May 1927 would lead one to think that there was no problem.

Canberra Ceremonies.

DUKE OF YORK AS SPEAKER.

Listeners-in have had little opportunity of hearing the Duke of York over the air, but those who have had agreed that his Royal Highness has a voice excellently adapted for broadcasting. He speakers [sic] clearly and distinctly, and carefully gives every syllable of each word sufficient and proper emphasis. His speech at the dinner given in Parliament House, Melbourne, by the Federal Government - the most important pronouncement yet made in Australia by the Duke of York - was effectively broadcasted by 3LO [a Melbourne radio station]. Listeners were surprised by the striking clearness of the pronunciation and the effectiveness with which the whole speech came over the air. ...

Dealing with the manner of speech adopted by the Duke of York a 3LO announcer states:- "There is not the slightest suggestion of a stammer in his speech. I understand that once this defect existed and it was cured by silence. Certain words, certain consonants, present hurdles to a nervous speaker. He knows them; he anticipates them. By maintaining a few seconds silence, it is possible to gain the assurance necessary to overcome the obstacle. It is in this way, and this way only, that his Royal Highness's speaking is affected. His words are perfectly formed, and in a considerable experience of hearing him speak, in public and in private, I have never once heard him stammer or take two shots at a word. I have known him pause for as long as 20 seconds, and then proceed with easy, fluent words in a resonant, musical, easy tone. He has long recovered from the embarrassment that once made him flurried at these pauses, and his own unconcern quickly puts the listener at ease. The pauses are usually no longer than good speakers affect for rhetorical purposes. Would to Heaven that all public speakers spoke like his Royal Highness. What a world of trouble we would be saved."

The Daily Guardian of Sydney of 10 May, reporting on the Canberra ceremonies, stated that the

DUKE WAS NERVOUS

Inside the House, as the Duke began his reply, the Duchess was obviously nervous. Her arms hung straight down, and her fingers convulsively closed and opened.

In the first sentence the Duke halted. He paused every few words, but there was apparently no stutter.

After the first few sentences he spoke smoothly and audibly, and the Duchess, in obvious relief, crossed her arms and regained her nerve.

Plainly the Duchess shares all the Duke's anxieties, and mothers him through the troubles of speechmaking. Her eyelids fluttered during every long pause, her throat contracted whenever his nervousness showed, and her face flushed along with his when he seemed momentarily embarrassed.

Sydney's The Bulletin of 12 May commented on the Duke's speech outside Parliament House:

The Duke's simple words ... were delivered in hesitant style but with crystal-clear enunciation.

The Duke himself was happy and proud of his Senate speech. He wrote:

I was not very nervous when I made the Speech, because the one I made outside went off without a hitch, & I did not hesitate once. I was so relieved as making speeches still rather frightens me, though [Lionel] Logue's teaching has really done wonders for me as I now know how to prevent & get over any difficulty.

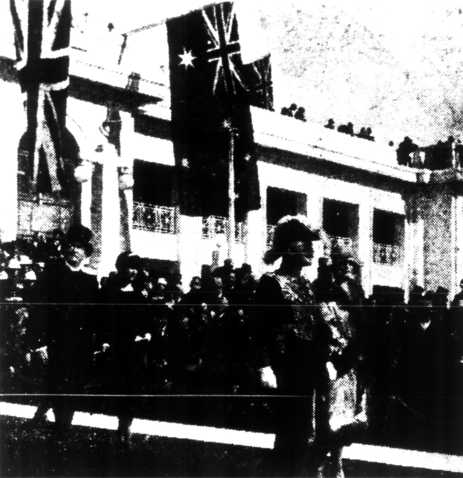

Image courtesy of the National Library of Australia

| This image was published in a newspaper in December 1949

and is captioned

Taken from de Forest's first sound-on-film recording in Australia on the opening of the Federal Parliament at Canberra by their present Majesties. The Governor-General, Lord Stonehaven and Lady Stonehaven are followed by Mr. S. M. (now Lord) Bruce and wife.Why wasn't a picture showing the Duke and Duchess published? Is this the only image the journalist had from the film? |

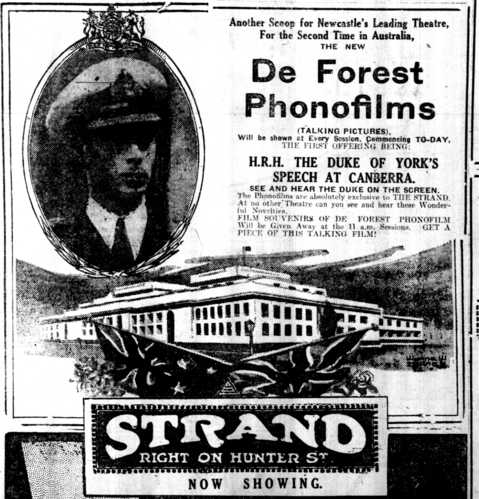

Phonofilms were, apparently, quite a success at the Strand cinema in Newcastle, New South Wales, one of the few venues in Australia that were wired for phonofilm sound. The advertisement below is from the Newcastle Morning Herald of 30 May 1927, for the first showing of phonofilms at that theatre. Their season of phonofilms, as supports only, ran until August 1927, the programme being changed several times over this period.

The problems with the film of the opening of Parliament House did not go unremarked. In the 31 May edition of the Newcastle Morning Herald the following review appeared.

At the Strand theatre yesterday Newcastle had its first opportunity of seeing and hearing the De Forrest phono films, [sic] the first really successful efforts in a new era of cinematography, the talking picture, and all who saw them endorsed them as the scientific marvel of the age. The main feature of the four films shown was "The Opening of Canberra," but it was unfortunate that it did not come up to expectations. The photography was all that could be desired, but due to what is stated to have been official interference by the authorities, the promoters were unable to take the recording machine to Canberra, and the talking part of the picture had to be taken over the wireless. Although it came out fairly well under the circumstances, there was much to be desired, but when the next picture which had been made in the studio was begun, the audience showed amazement. It certainly seemed as if the person depicted on the screen was speaking from there, the action of moving the lips and the reproduction of the voice synchronising. Two other pictures were shown, and it was evident that the results of years of experiment in the picture industry had not been fruitless. Mr. S. W. Hawkins, general manager of the De Forrest Company, an Australian organisation, was present at the screening, and he expressed his pleasure at the results. ... |

Image courtesy of the National Library of Australia

|

|

Copyright © 2011 – 2024 Tony Martin-Jones | FILM HISTORY INDEX |

Edition 3·2 (2024-11-17) [First edition in 2011-03] |