Marius Sestier in Australia

The first motion pictures shot and produced in Australia

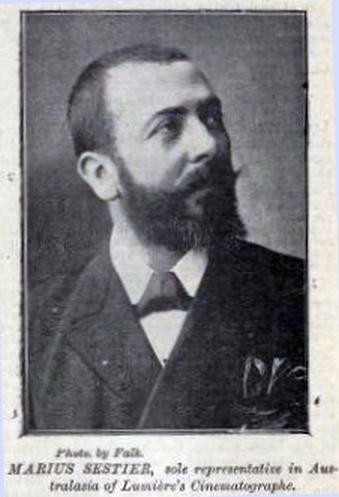

Marius Sestier soon after his arrival in Sydney

Summary list of Marius Sestier's activities in Australia

- 16 September 1896: Marius Sestier and his wife arrived at Sydney, New South Wales on board the F.M.S. Polynésien from Colombo, Sri Lanka.1 They had, in fact, come from Bombay [Mumbai], India.

- 18 September 1896: Sestier gave a private demonstration of the Lumière cinématographe at the Lyceum Theatre, Sydney.2

- 26 September 1896: Sestier gave another private demonstration at the Lyceum Theatre.3

- 28 September 1896: first exhibition of the cinématographe to the public at 237 Pitt Street, Sydney, the Salon Lumière.4

- 4 October 1896: probably filmed the ferry, s.s. Brighton, arriving at Manly. This was possibly the first motion picture filmed in Australia.38

- 27 October 1896: gave last exhibition of this season of the cinématographe in Sydney.5

After the last show on this day, the first successfully produced local film, of the s.s. Brighton at Manly, was shown. - 28 October 1896: the Sestiers travelled to Melbourne, Victoria by train.6

- 31 October 1896: filmed at the VRC Derby races at Flemington racecourse, Melbourne.7

- 31 October 1896: gave the first exhibition of the cinématographe at the Princess' Theatre, Melbourne.8

- 3 November 1896: filmed at the Melbourne Cup races at Flemington racecourse.9

- 19 November 1896: gave the first screening of one of the Melbourne Cup films at the Princess' Theatre.10

- 20 November 1896: final screening at the Princess' Theatre.11

- c. 22 November 1896: returned to Sydney.12

- 24 November – 8 December 1896: exhibitions at the Criterion Theatre, Sydney.13,14

- 9 December 1896 – 6 March 1897: exhibitions at 478 George Street, Sydney.15,16

Sestier left the later exhibitions in Sydney in the hands of others. (But not of H. Walter Barnett, who had gone to Melbourne, and later, to England.) Another Lumière cinématographe arrived in Sydney on 11 December 1896, and Sestier took it to Adelaide, South Australia.

- 23 or 24 December 1896: the Sestiers arrived in Adelaide by train.17,18

- 24 December 1896: rehearsal exhibition at the Theatre Royal, Adelaide.18

- 26 December 1896 – 29 January 1897: exhibitions at the Theatre Royal.19

Leaving Wybert Reeve in charge in Adelaide, Sestier made a brief return to Sydney by train. He was there able to pick up a third cinématographe that had arrived on 8 January 1897.

- 14 January 1897: Sestier gave a benefit exhibition for the French Benevolent Society and the French Library of Sydney.20

He went back to Adelaide for the end of the Theatre Royal season. After that, Reeve took the (second) cinématographe on tours of country towns.

- 27 January 1897: the Sestiers left Adelaide on board the R.M.S. Oceana for Western Australia, with the third Lumière cinématographe.21

- 30 January 1897: the Sestiers arrived at Albany, Western Australia.22

- 1 – 27 February 1897: at Ye Olde Englishe Fayre at Perth, Western Australia.23

- 2 – 7 March 1897: at the Theatre Royal, Coolgardie, Western Australia with Ye Olde Englishe Fayre company.24

- 9 – 15 March 1897: at the Miners' Institute, Kalgoorlie, Western Australia with Ye Olde Englishe Fayre company.25

- 10 March 1897: filmed at the Great Boulder mine, near Kalgoorlie.35 He may also have filmed there on a later day.

- 16, 17 March 1897: return visit to Coolgardie with Ye Olde Englishe Fayre company.26

- 19 – 30 March 1897: a final season at Ye Olde Englishe Fayre at Perth, Western Australia.27

- 2 April 1897: left Albany on the R.M.S. Rome for Sydney.28

- 10 April 1897: the Sestiers arrived in Sydney aboard the R.M.S. Rome.29

- (Nothing indicates that he ran further exhibitions.)

- 19 May 1897: the Sestiers left Sydney on board

the F.M.S. Polynésien for Marseille, France.30

- 23 June 1897: they arrived at Marseille.31

There is no evidence that Sestier exhibited a cinématographe at Broken Hill, New South Wales. (But Wybert Reeve did.) And despite passing through Albany on his way both to and from Perth, he did not exhibit there either. (Though Carl Hertz put on shows at Albany during his transit visits in 1897.) And Sestier did not visit New Caledonia.37

During the Sestiers' time in Sydney, they (supposedly) stayed with the Boivin family at Glebe.39 Eugène Boivin was secretary to the French consul in Sydney, and resided in the large mansion Strathmore in Glebe [Point] Road41 for several years.

The first shows in Sydney

On the morning of 16 September 1896, Marius Sestier and his wife arrived in Sydney Harbour aboard the French mail steamer Polynésien. They had left Bombay, India on 26 August, having spent 2 months there, during which time Sestier had shown the first projected motion pictures in India. He may well have been hoping to repeat such a first when he reached Sydney; after all, he had been commissioned by the Lumières both to exhibit the cinématographe in India and Australia, and to make films of local subjects. For on-board evening entertainment while the ship steamed across the Indian and Southern Oceans, Sestier had shown "animated photographs" with his Lumière cinématographe.

The ship had stopped at Melbourne, Victoria, and actor-manager-entrepreneur Harry Rickards and family had boarded to travel to Sydney too. Rickards went there to prepare for his next big show at his Tivoli Theatre, which would include the eminent illusionist, Carl Hertz, and his presentation of another cinematographe, a Theatrograph from Robert W. Paul of London. Hertz had been performing and showing his cinematographe at Rickards' Opera House in Melbourne since 15 August, and is now credited with being the first to show projected motion pictures in any Australian colony. No doubt Rickards and Sestier would have discussed the new "marvel of the century"; possibly Sestier did one last evening exhibition on the way from Melbourne to Sydney. Maybe Rickards tried to strike a deal with Sestier for running a show with him as manager; or maybe not, as Rickards already had arrangements with Hertz, whom he had booked in England late the previous year.32

On the second day after his arrival in Sydney, Sestier gave a private demonstration of the cinématographe at the Lyceum Theatre, courtesy of George L. Goodman, acting manager for J.C. Williamson and George Musgrove. He beat Hertz by a day (in Sydney), but Hertz's shows were open to the public. But neither was the first exhibitor in Sydney, for Joseph Francis MacMahon had also given a private demonstration of yet another cinematographe, a "kinetomatograph", on 27 August at the Criterion Theatre. (MacMahon did not get an exhibition venue in Sydney and took his machine to Brisbane, Queensland.)

Why was Sydney Sestier's first Australian destination?

And had his arrival been anticipated by anyone there, or did he turn up "out of the blue"?

The Lumières had used the agents for their photographic products in the various

countries that were visited by their cinématographe operators as points of contact

for these operators, so possibly there was such an agent in Sydney for Sestier to meet.

But his arrival was unheralded:

as one contemporary newspaper put it,

"He came out unostentatiously in one of the French mail-boats, and was immediately seized

upon by Mr. Walter Barnett, of the Falk Studios, who, in conjunction with

Mr. C. B. Westmacott, arranged for him to exhibit his wonderful machine in Pitt-street.

"

Sestier's first showing must have been of the nature of a test run, to demonstrate what his machine was capable of. Barnett and Westmacott set Sestier up in his own "theatre" – simply a shop that had recently been an auction rooms and then that of a tailor who had gone bankrupt – to show the cinématographe; at 237 Pitt Street it was given the title of Salon Lumière, and was Sydney's first venue dedicated to projected motion pictures, and thus, in that sense, its first cinema. (It was not Australia's first cinema, however, because Joseph MacMahon was again ahead, having opened a cinematographe-only show in the Royal Arcade, Brisbane, on 26 September.) The room was not open to the public until 28 September, though another private showing was given at the Lyceum Theatre on 26 September.

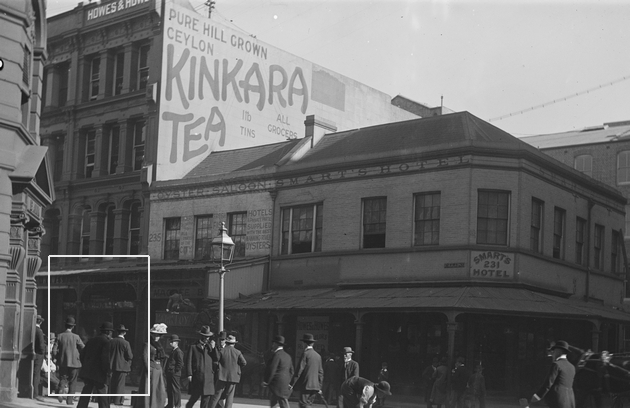

Pitt Street, Sydney, at its intersection with Market Street

The front of the shop at number 237 Pitt St is indicated by the light rectangle

Both Sestier's and Hertz's cinematographe exhibitions were extremely successful

and attracted large audiences –

they "boomed", in the talk of the day.

As The Bulletin noted:

"Sydney is gradually going mad over this new invention, and the signs are that the

cinematograph is going to rage virulently for a time.

"

There would have been rivalry between the two, but there were enough interested

people in the city to keep both theatres well occupied.

Besides, the shows were of different styles:

Sestier showed films only, while Hertz was part of a variety company which included

musical and comedy "turns".

But Sestier had many more films to show than Hertz, to keep people coming back by

changing the programme;

and he ran many more, because only half-an-hour long, shows throughout the day.

Hertz was bound by his contract with Rickards and had to finish in Sydney on

14 October 1896 so that the show could go elsewhere.

So Sestier had the Sydney cinematographe scene all to himself.

During this period of exclusivity, the Salon Lumière was visited

by various VIPs:

the Governor of New South Wales and Lady Hampden;

the Governor of Queensland and Lady Lamington;

the Primate; the Bishop of Newcastle; and the Bishop of Goulburn.

His continued success was even noted in the London press:

"MESSRS WESTMACOTT AND BARNETT made a wise speculation in engaging Lumière's

Cinématographe, for the place is full some sixteen times every day.

"

But the Spring Racing Carnival season in Melbourne had started, and the southern capital

was expecting a large influx of visitors, primarily for the Melbourne Cup horse race

on the first Tuesday of November: 3 November in 1896.

J.C. Williamson and George Musgrove, as lessees and managers of the Princess' Theatre

in Melbourne, had decided to put on another season of the spectacular theatre piece,

Djin-Djin, which had been enormously successful at an earlier staging.

The presentation of another version of the show would capitalise on the presence

of the large number of visitors to Melbourne, as well as the local population who

would want to see it again.

To increase the drawing power of the show, "numerous special features" were included,

"the most interesting being the only authentic ORIGINAL LUMIERE CINEMATOGRAPHE

",

with Marius Sestier directing its operation.

(Sydney's The Daily Telegraph commented:

M. Marius Sestier, who represents the Lumiere Cinematographe in Australia, is in the rare position of having to leave immensely profitable business. The exhibitions at 237 Pitt-street continue to attract great numbers of people, but engagements made for the display of the Lumiere invention in Melbourne have to be kept, ....Not that there wasn't going to be plenty of business in Melbourne, of course!)

Probably during this last couple of weeks in Sydney, Sestier had started fulfilling another of his obligations as a Lumière operator, to make films of local subjects. Only three films are known from this time: Passengers leaving s.s. Brighton at Manly, Sydney on Sunday afternoon and two films of the New South Wales Horse Artillery at drill at Victoria Barracks, Sydney. The first of these was shown publicly for the first time following the last exhibition in Sydney (for the time being) on 27 October. After the show Walter Barnett announced that there were more local films to come, no doubt anticipating the films to be made at the Melbourne Cup.

To Melbourne for the 1896 Cup

Return to Sydney

When Sestier left Sydney at the end of October, there was no other cinematographe

show in town.

But the public were hungry for "animated photographs" or "living pictures".

James MacMahon (a brother of Joseph) had, rather fortuitously, returned to Sydney on 24 October

from a flying visit to Europe, during which he had purchased a Demeny Chronophotographe,

which was another type of cinematographe but with 60 mm wide film.

Seeing that Sestier was about to go to Melbourne, he struck a deal with George L. Goodman

and Charles B. Westmacott to move in to the Salon Lumière,

smartly adjusting the cinema's name to Salon Cinematographe.

But he didn't get up and running as quickly as he had wanted to.

He initially advertised to start on Saturday, 31 October, but to

"enable a better system of ventilating the premises to be completed

",

the next opening date was to be Monday, 2 November.

But this date was also slipped (for no publicised reason), and he finally opened

on Saturday, 7 November.

Sestier and Barnett, knowing they would return to Sydney, were not pleased:

from Melbourne they both issued notices to the Sydney newspapers disassociating

themselves from MacMahon's show.

The last presentation of Djin-Djin with the Lumière cinématographe at the Princess' Theatre in Melbourne was on 20 November 1896. In spite of a note in Melbourne's The Age that the cinématographe would stay in that city, the Sestiers returned to Sydney about 22 November, and on 24 November the Criterion Theatre became the new Sydney venue for the Lumière cinématographe.

When Sestier left Melbourne there was only one other cinematographe show on in town, in marked contrast to the four that he had had to compete with during the Melbourne Cup week. And on his return to Sydney, he only had James MacMahon to contend with. MacMahon had been doing exceptionally good business, with packed houses for all his sessions (if one is to believe the press reports); just before Sestier returned, MacMahon was noting in his newspaper advertisements that he had had 20,000 people visit the Salon Cinematographe in just 2 weeks. And on 24 November, when Sestier started again, this count had increased to 25,000 – and MacMahon proudly kept announcing further increases over the following weeks and months.

Fortunately for Sestier, he had something no one else had: locally-made films, especially those taken at the Melbourne Cup.

To be continued ...

Sestier goes west

Perth, Western Australia, although not nearly as populous a city as Sydney or Melbourne nonetheless needed entertainment; and also the recently established towns of Coolgardie and Kalgoorlie, which grew quickly following the discoveries of gold in the region, were markets for shows. Leaving Wybert Reeve to look after cinematographe exhibitions in South Australia, on 27 January 1897 the Sestiers boarded the P. & O. Company's R.M.S. Oceana at Port Adelaide to steam to Albany, Western Australia, where they arrived on 30 January. From there they caught the train to Perth.

Sestier had been engaged by George A. Jones and George R. Lawrence to exhibit the cinematographe

as part of their Ye Olde Englishe Fayre show, which was held outdoors on a large plot

on the main street of Perth.

This mixture of acts had been running in Perth for three months when Sestier joined.

The advertising hype promoting the cinematographe billed it as "The Greatest Event

in the Annals of Theatrical History of W.A.

" and "the Most Important Engagement

ever made for the West

"!

The first exhibition of a Lumière cinématographe in the colony of

Western Australia took place on the night of 1 February 1897.

(But, yet again, this was not the first time a cinematographe had been shown there,

that having been on 21 November 1896 by Frank St. Hill,

who had an Edison machine.)

Twelve films were shown on the first night, four of which were from the Melbourne Cup series.

If the newspaper reviews are to be believed, the cinematographe stole the show;

Jones and Lawrence's later advertisements proclaimed that over 5000 people paid

admission one night, and "that Ye Olde Englishe Fayre grounds have been filled to the

utmost limit allowed by law every night of the present extraordinary season

".

The cinématographe exhibitions ran at Perth until 27 January, when

"[t]he repertoire of pictures brought with the Lumiere cinematographe to the Fayre

by M. Sestier has now been exhausted

".

On this last night there were two showings, at which the "most attractive of

the pictures

" were presented.

Ye Olde Englishe Fayre company then took their show to the Theatre Royal, Coolgardie, travelling the approximately 560 km by train on the railway line that had been opened only 10 months earlier. They performed there from 2 March through 7 March. Again, the best of the Melbourne Cup films were featured, and the programme was varied each night. (Once again, Sestier had been preceded by Frank St. Hill with his Edison cinematographe: St. Hill had exhibited first at the New Mechanics' Hall on 9 January 1897. And up to a week and a half immediately prior to the Lumière cinématographe being shown in Coolgardie, H. Fein had been exhibiting a cinematographe at the Royal Cremorne Gardens.)

Their next venue was not far, about 60 km, away, at the Miners' Institute, Kalgoorlie. They played there from 9 March through 15 March. However, only one of the Melbourne Cup films is mentioned in a review, and none is listed in the advertised programmes. Maybe the films had become worn out, or possibly the audiences were not interested in old news. (As ever now, Sestier was not first with a cinematographe: St. Hill had exhibited on 22 January.)

While at Kalgoorlie, Sestier shot at least one film of goldmining operations in the area. (See below.)

The company then headed back to Perth, putting in a further two nights at the Coolgardie Theatre Royal on 16 and 17 March on the way.

Curiously, in the newspaper advertisements, reviews, and reports of the shows in Coolgardie and Kalgoorlie, there is no mention by name of Sestier.

Sestier did a final run with Ye Olde Englishe Fayre in Perth from 19 through 30 March. New pictures were advertised, even after, as noted above, the selection supposedly had been exhausted; whether this was simply advertising hype or if, in fact, Sestier had acquired further films is not known; possibly films used in Sydney (or Adelaide) had been sent to him.

On 2 April 1897, Marius and his wife boarded the R.M.S. Rome at Albany to return to Sydney, which they reached on 10 April.

Coda

The last 6 weeks of the Sestiers' stay in Australia are something of a mystery. (As are their last 2 weeks in Bombay.) Other than Marius' attendance at the ceremony of Denis O'Donovan's investiture with the French Légion d'Honneur on 12 April, no mention of their movements in this period has been found, and it is likely they passed the time having a rest from exhibiting and maybe travelling.

At 1 p.m. on 19 May 1897, the Sestiers left Sydney on board the F.M.S. Polynésien. And although the ship's agents had guaranteed to arrive at Marseille in time for passengers to get to London for Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee celebrations on 22 June 1897, they did not deliver, for the steamer arrived on 23 June.

Sestier's film output

One of Sestier's tasks for the Lumières was to make films of Australian subjects, which would be added to the collection they were building up with the help of other travelling operators. Sestier is now best known for his and H. Walter Barnett's films of the Melbourne Cup day of 1896, which are dealt with separately; some of these films were sent to France and preserved, and they are available for us to view today.

But they weren't the only films Sestier made in Australia, nor were they the first. Other films attributed to him and, possibly, Barnett that are mentioned in advertisements, reviews, and reports are the following:

- Passengers leaving s.s. Brighton at Manly, Sydney on Sunday afternoon

- New South Wales Horse Artillery at drill at Victoria Barracks, Sydney (2 films)

- [General] Post Office, Sydney, from George Street

- Other films shot around Sydney Harbour

- Sea and Breakers, Coogee [Bay]

- Bathing at Manly

- Elizabeth Street, Sydney

- Sydney Domain on Sunday afternoon

- The Western Australian goldfields films

- Patineur grotesque

| The first of these is generally considered to be the first motion picture successfully produced in Australia. It was probably filmed on Sunday, 18 or Sunday, 25 October 1896,33 and was shown to the public for the first time on 27 October after the last exhibition of Sestier's first season in Sydney. Why didn't this film end up in the Lumière collection? It was, for Sydney, with a major harbour, the local equivalent of an Arrival of a train film, of which there are several from around the world. Was the film sent to France but was somehow lost? Or did Sestier, for some reason, not send it? It is a major cultural and artistic loss that no surviving copy is known.34 |

|

The two NSW Horse Artillery films appeared for the first time (with the Manly ferry film) on 24 November 1896 at the first showing of the Melbourne Cup films at the Criterion Theatre, Sydney. Again, no copy of either is known to exist.

Mention of the Post Office, George Street film has been found in only three places: in reviews in the Sydney papers Evening News of 19 December 1896 and The Daily Telegraph of 21 December 1896; and on a copy of a handbill that has the same list of films as in the Evening News review. Why was it never mentioned again, in an advertisement or review: was it not popular?

Jack Cato says (in his hagiography36 of H. Walter Barnett) that Sestier

"took his camera down to the harbour and made a series of pictures of the bays, the foreshore,

and the little paddle-steamers

".

One wonders how much film stock Sestier had with him!

The fifth film referred to above, of Coogee or Coogee Bay, may be one of these films

that Cato said were made, though it is more likely to be one of the European

Sea and Breakers films that were extremely popular with audiences.

It was named on programmes in Queensland in 1897, and it is possible that anyone

there who saw it would not have been able to identify the location of its scene.

There were other occasions where the European films were claimed to have been

made in the country where they were shown.

It is also possible that the film was not made by Sestier but by another operator,

maybe even Georges Boivin, who was managing these Queensland shows.

Similarly, the Bathing at Manly film, which is only mentioned in one review,

is probably the very popular Lumière standard, The Baths of Diane, Milan

(where possibly "Milan" is confused with "Manly"),

or Sea Bathing (or Surf Bathing).

There are two references to the Elizabeth Street film, in advertisements in The Brisbane Courier of 26 June 1897 and The Age (of Melbourne) of 4 October 1897. The second mention states that it was a view of the corner of Elizabeth and King Streets, Sydney. Again, the film may have been made by someone other than Sestier. Or it may have been the film of the Post Office, George Street, or one of the Lumière films of a street in a European city.

The Sydney Domain film is almost certainly hypothetical.

In The Sydney Morning Herald review of the first showing of the full suite of Melbourne Cup

films, reference is made to "the stream of people crossing from Hyde Park past St. Mary's

into the Domain on Sunday afternoon interrupted by the passing cable trams

".

But in context this appears to be more of a suggestion for a film subject than a description

of an existing film.

It is not mentioned in any other review of this show, nor in any advertisement,

nor in any review of any subsequent exhibition.

Ted Breen, who was employed at the Criterion Theatre, Sydney, in some recollections

published in Everyones magazine in January 1924, says that a film of

"a stream of people crossing from Hyde Park past St. Mary's into the Domain,

on a Sunday afternoon" was shown with the Melbourne Cup films.

He obviously needed help with his recollections, and had a copy of the paper to hand.

(Breen also recalls seeing a film of "employees leaving the Government Printing Office".

This was a film by Mark Blow, and in the advertisement for Blow's Polytechnic on

26 February 1898, it is identified as

"EMPLOYEES LEAVING GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, Sydney, 1 o’clock, Thursday, 24th instant

".

If only all (early) films had such a timestamp!)

The Kalgoorlie Miner newspaper of Thursday, 11 March 1897 reported the following item of local news:

A novel experience in photography was afforded to the many visitors to the Great Boulder mine on Wednesday afternoon. This was the taking of a series of pictures for reproduction in the cinematograph. The view taken was the main shaft, with the cages ascending and descending, and the visitors, being stationed on the landing stage at the top of the poppets, walked down the steps and across to the mine office, where the instrument was placed in position. In all about forty ladies and gentlemen took part in the promenade, and, as the view showing the action of raising the ore to the surface and the crowd descending from the landing stage is to be exhibited at the Empire in London, English audiences will probably form an erroneous idea of the manner in which the employés of the big mine go to work. The film on which the view is taken passes quickly automatically across the camera to secure the effect of continuity, and no doubt the view showing the working of the mine will be looked at with interest by English investors. Unfortunately, the day was too dull to enable the battery at work to be taken, but if bright weather prevails to-day this scene, showing how the gold is extracted from the ore, will probably be obtained.And the first review in The West Australian of the return show in Perth after the tour of the Westralian goldfields notes: "

When at the goldfields views were taken by this invention of the operations at several of the most successful mines, for transmission to the Eastern colonies."

A remarkable point about the local news item above is that the description of the contents of the film was made at the time of filming (rather than at the time of exhibition).

It is unlikely that Sestier had the facilities to develop films with him on his travels, and may not have been able to do so even at Perth. There is no further mention of any goldfields film in the advertisements or notices for the Perth shows, nor in any subsequent newspaper article for a Lumière cinématographe show, even after Sestier had left Australia. What became of them? It is possible that they were not successfully developed or printed.

And what of the film Patineur grotesque? Only in about 1996 was it determined that it was made in Australia, presumably by Sestier. But it turns out to be an historian's nightmare, and it deserves a separate page: see patineur-grotesque.htm.

In summary, other than the Melbourne Cup films there are five films that we can definitely attribute to Sestier (and Barnett): the Manly ferry film; the two films of the New South Wales Horse Artillery; the Post Office, George Street; and Patineur grotesque. And the only one of these of which we have a copy is Patineur grotesque.

One must wonder if Sestier ever contemplated filming that quintessential Australian animal, the kangaroo. As a subject this would surely have appealed to anyone elsewhere in the world who had heard of such a creature. The fixed field of view of the Lumière cinématographe would have made filming a 'roo difficult, unless the animal itself were somehow constrained. But it should have been possible.

Assessment of Sestier's work in Australia

Despite his (jointly) making the first motion pictures in Australia – and how much credit H. Walter Barnett should be given for these might never be fully determined – Marius Sestier did not over-extend himself in presenting cinematographe shows when compared with other exhibitors at the time or soon after. He visited four capital cities for extended seasons, and his only venture to the country was a brief visit to two towns in the Western Australian goldfields. This should be contrasted with the shows of Carl Hertz and Wybert Reeve, who both toured the country extensively. Admittedly, Hertz and Reeve had considerable experience in touring shows; nonetheless, Sestier could not have been ignorant of the ways of show business at that time. The comparison with Hertz may not be fair though, because Hertz's act was more than just a presentation of a cinematographe, and included his illusions and conjuring; Hertz also had a hard-working manager who arranged his shows.

But Sestier should be compared with his contemporary Lumière operators, such as Alexandre Promio, Charles Moisson, and Gabriel Veyre. These operators travelled extensively and each produced many films which ended up in the Lumière collection.

As a final assessment, it must be concluded that Sestier's exploitation of the Lumière cinématographe was second-rate.

References and notes

Many events listed above were mentioned in several newspapers of the day, both in advertisements and in reviews and reports. Typical references are given below.

[1] The Sydney Morning Herald, 17 September 1896, p.4a, Shipping.

[2] The Sydney Morning Herald, 22 September 1896, p.6c, Lumiere's Cinematographe.

[3] The Sydney Morning Herald, 28 September 1896, p.3f, Lumiere's Cinematographe; The Daily Telegraph, 28 September 1896, p.6e, Lumiere's Cinematographe.

[4] The Daily Telegraph, 29 September 1896, p.6d, Lumiere's Cinematographe.

[5] The Sydney Morning Herald, 28 October 1896, p.8b, The French Cinematographe.

[6] They could only have travelled by ship or by train, and as their names haven't been found in the shipping departure lists, they most likely caught an overnight mail express train to Melbourne. They were there on 29 October because The Sydney Morning Herald published, on 30 October, a note from Sestier giving his address as the Princess' Theatre.

[7] This was the date of the Derby in 1896 and we know of films from that day.

[8] The Age, 2 November 1896, p.8b, Princess Theatre - Djin Djin.

[9] This was the date of the Melbourne Cup in 1896 and Sestier and Barnett made films then.

[10] The Age, 20 November 1896, p.8b, Royal Institute for the Blind, Lady Brassey's Appeal.

[11] The Age, 20 November 1896, p.8i, advertisement.

[12] Nothing specific about their return has been found. They almost certainly went by train.

[13] The Sydney Morning Herald, 25 November 1896, p.8b, The Lumiere Cinematographe.

[14] The Sydney Morning Herald, 8 December 1896, p.5c, The Lumiere Cinematographe.

[15] The Sydney Morning Herald, 9 December 1896, p.2c, advertisement.

[16] The Sydney Morning Herald, 6 March 1897, p.2e, advertisement.

[17] The Register, 23 December 1896, p.3h, Theatre Royal.

[18] The Register, 25 December 1896, p.6e, Theatre Royal.

[19] The Advertiser, 28 December 1896, p.6e, Theatre Royal.

[20] The Daily Telegraph, 15 January 1897, p.3h, Lumiere Cinematographe - Benefit Exhibition.

[21] The Advertiser, 28 January 1897, p.4a, Shipping News. Their name is spelled "Lester".

[22] The West Australian, 1 February 1897, p.4a, Shipping Intelligence; Arrivals. Again, they are listed as "Lester".

[23] The West Australian, 1 February 1897, p.1f, Entertainments;

The West Australian, 27 February 1897, p.5e, Amusements.

[24] The Coolgardie Miner, 2 March 1897, p.2g, Amusements;

The Coolgardie Miner, 6 March 1897, p.2g and p.4g.

[25] The Kalgoorlie Miner, 6 March 1897, p.4c, Public Notice;

The Kalgoorlie Miner, 15 March 1897, p.2e, Amusements.

[26] The Coolgardie Miner, 16 March 1897, p.2f, Amusements;

The Coolgardie Miner, 17 March 1897, p.2g, Amusements.

[27] The West Australian, 20 March 1897, p.5g, Entertainments;

The West Australian, 30 March 1897, p.1, Entertainments.

[28] The Albany Advertiser, 3 April 1897, p.3f, Shipping Intelligence.

[29] The Sydney Morning Herald, 12 April 1897, p.4a, Shipping.

[30] The Daily Telegraph, 19 May 1897, p.11d, Shipping.

[31] The Sydney Morning Herald, 25 June 1897, p.6h, Shipping Reports; The Mail Steamers.

[32] There is no evidence that Sestier and Rickards met on the ship, but it seems highly unlikely that they didn't. Both were top-dollar-paying passengers, and shared the same deck space and dined at the same table. Other passengers might have known who Rickards was and of his theatrical business, and would likely have mentioned the on-board evening screenings of the cinématographe; the word would certainly have gone around the ship that there was an "animated photographs" man on board. And possibly Sestier did one final exhibition on the way to Sydney.

So assuming they did meet, did Rickards try to make a deal with Sestier? (Rickards certainly knew the cinématographe was a money maker.) If Sestier didn't accept, why not? It might have depended on whether or not Sestier already had an arrangement in place to show his films. And if he did accept, what happened later?

[33] Considering that the development and duplication of a 17 m length of film had never before been accomplished in Australia, it might well have taken longer than the two days between 25 and 27 October to go from shooting to presentation of the film.

[34] The Melbourne Cup films have numbers 418 through 423, and 652, in the Lumière catalogue. Film number 424 is Débarquement d'une [bateau-]mouche, a film of passengers leaving a boat, supposedly in Lyon. I thought that possibly no. 424 had been misidentified and was in fact the Manly ferry film, so compared an image from it (kindly provided by Luke McKernan) with photographs of the ferry Brighton (from the National Library of Australia). There is no doubt that the ferry in no. 424 is not the Manly ferry Brighton.

[35] The Kalgoorlie Miner, 11 March 1897, p.2e, Items of News.

[36] Cato does not warrant a citation, as for decades his book has poisoned the historiography of early Australian film presentation and production.

[37] The Noumea newspaper La France Australe was misinformed and stated that Sestier had arrived in Noumea on the Polynésien. They also thought that he would spend some time there and show the cinématographe. (La France Australe (Noumea, New Caledonia), 30 September 1896, p.2b, Le Cinématographe)

[38] There is good reason to believe that the first film taken by Sestier (and thus the first film shot) in Australia was Patineur grotesque. However, until the date of filming of this is determined, the Manly ferry film holds the honour of first Australian film.

[39] I do not know the source for this detail so won't vouch for its veracity. The information comes from the NFSA though they don't state their source. In Sestier's accounts book several payments for board are listed, so if they did stay with the Boivins they nevertheless paid their own way.

[40] The Bulletin, 10 October 1896, p.8d.

Note that this image is correctly oriented laterally:

Sestier's outside jacket pocket is on his left side, and the jacket is closed

left side over right.

[41] Strathmore had previously been a ladies' college for the University of Sydney, and from late 1899 for several decades was run by the Church of England as a "rescue home" for girls and women. In the late 1960s it was demolished and the site of the building and its grounds are now occupied by blocks of flats.

[42] Detail from Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales:

Series 01: Glass negatives of Sydney and suburbs ca. 1900-1914 /

Mrs. Arthur George Foster; Call Number:

From the business signs that are visible in the photograph it can be determined

that it was taken between 1901 and 1903, several years after Sestier was there.

The block of buildings that comprised numbers 237 through 247 Pitt Street

was built in 1882

(The Sydney Morning Herald,

14 March 1882, p.10c, Improvements in Sydney.)

for Wright, Heaton, and Co., who were the owners until 1910.

(Evening News (Sydney),

9 July 1910, p.2e, Sale of City Property.)

Another view of this building, at a more oblique angle and taken c. April 1893, is

PITT STREET SYDNEY NEAR MARKET STREET.

Nothing is written about exactly where Sestier's "salon" was situated in the building at 237 Pitt Street, beyond one reference to it being in the "shop". (Daily Telegraph (Sydney), 12 October 1896, p.3h, Amusements., Salon Lumiere.) Presumably this was a room or rooms at street (entry) level.

| Copyright © 2010 - 2019 Tony Martin-Jones | FILM HISTORY INDEX | Edition 7.5 (2019-11-18) |